This is an unpublished paper I wrote in the Fall of 2024 about the history of the term “Anthropocene”. As the BIGGEST next thing, the Anthropocene excavates as it flattens, unearthing publishing gold in a universal crisis narrative that might critique power, but stops a mile short of any challenge to power that might threaten ones academic career or social status. This paper was written for a paleoenvironments class, so be prepared for some geological time scale nerd shit.

ABSTRACT: The Anthropocene was officially rejected as a new geological epoch in February 2024 by the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy (SQS), even as it remained a cultural zeitgeist and increasingly popular shorthand for describing the environmental polycrisis. The Anthropocene took a winding 25-year path from the time it surfaced in the infamous Crutzen and Stroemer paper, to being flatly rejected as a new epoch on the Geological Time Scale. In their coordinated efforts to nurture the normative conditions necessary to place 75 years of industrial civilization in the deep history of geology, the Anthropocene Working Group (AWG) succeeded in raising the profile of the Anthropocene as a universal, global crisis that threatens the political and economic status quo. In this paper I follow the path of The Anthropocene to better understand how it combined Earth Systems science and geology to make normative statements about a future apocalyptic crisis caused by humans. I then use Indigenous philosopher Kyle P. Whyte’s concept of crisis epistemology to explore how proponents of the Anthropocene concept were able to normalize temporal qualities of unprecedentedness and urgency to mobilize resources for technological solutions that uphold the political and economic status quo.

Key words: Anthropocene, technofossils, crisis, urgency, unprecedentedness

Introduction

Don’t worry, we are still in the Holocene. With or without that coveted golden spike[1] bearing witness to the grubby fingers of industrial humanity, The Anthropocene concept isn’t likely to shrink away in shame after its rejection as an official new epoch on the Geological Time Scale. As of December 2024, Web of Science listed more than 16,000 research papers that mention the Anthropocene since the year 2000, peaking in 2023 at about 2000 research papers a year and only now showing signs of a slight decline[2]. There are dedicated journals and conferences, and the term has gained popularity outside of the academy among writers and activists concerned with climate change and environmental collapse. It seems that even though the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy rejected the idea that humans finally ended the Holocene for the entire Earth in the mid-20th century, there is a strong and persistent desire for a narrative that can subsume all manner of 21st century environmental, social, and political instability under the banner of urgency and crisis.

The common sense assumption that we are in a state of crisis related to climate change and the web of environmental catastrophes that humanity is currently facing are not neutral or objectively helpful for the human beings confronted by this existential threat. Like other dystopian stories about environmental collapse, there is political-epistemological work that the Anthropocene concept does as it consolidates data from the past and present to project apocalyptic narratives onto a universal future. The idea of humanity in general as a geological actor obscures the colonial power relations that are still playing out, despite the materiality of a small group of people with names who are each exponentially more responsible for our predicament than several billion people combined. The unprecedentedness and urgency that are bound up in the Anthropocene narrative ensure that the “solutions” and responses to the crisis will be bound up the political economic status quo.

[1] The Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) is also know as the ‘golden spike’.

[2] https://www.webofscience.com/wos/alldb/summary/ecbc5d83-bd7e-489b-be40-58b5870df3ab-01357a02f8/relevance/1

Anthropocene Working Group History

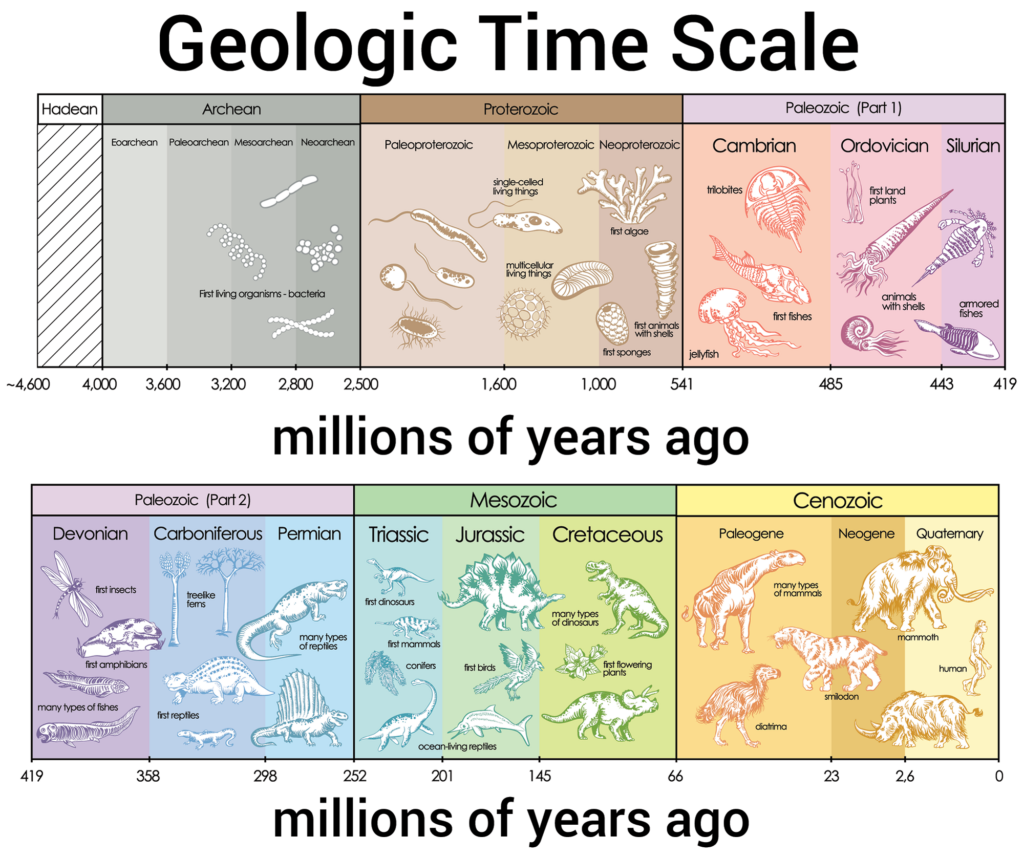

Geologists and other scientists concerned with the deep history of how the planet changed over the last two billion years orient the spans of time they are concerned with along the Geologic Time Scale. The Geologic Time Scale organizes linear time in intervals, with named eons, eras, periods, epochs, and ages nested hierarchically based on time-rock sequences. These intervals We find ourselves currently existing in the Quarternary Period, Cenzoic Eon, Holocene Epoch, and Meghalayan Age. The Holocene marks the last 11,600 years of warming after the last ice age, in which humans evolved and spread across the planet, developing a variety of cultures and civilizations along the way. All of human history, including the development of agriculture, cities, and written language occurred in this relatively stable period of time, as measured in ice cores, lake sediments, and other types of biological samples.

Earth Systems scientists in the early 21st century were some of the first researchers to use the term Anthropocene in their work studying changes in planetary-scale processes involving the climate, atmosphere, and biosphere. These scientists define the Earth System as “a single, planetary-level complex system, with a multitude of interacting biotic and abiotic components, [that] evolved over 4.54 billion years and which has existed in well-defined, planetary-level states with transitions between them” (Schellnhuber 1998). In recognizing that the primary driver of the Earth’s temperature over long periods of time is the energy balance, which involves interconnected systems and feedback loops, Earth Systems scientists measure signals of changes to the systems happening now that began in the (sometimes deep) past (Steffen et. al 2016). As such, they were the first scientists to declare that 11,600 years of Holocene stability had come to an end and that humans are the primary cause of these changes.

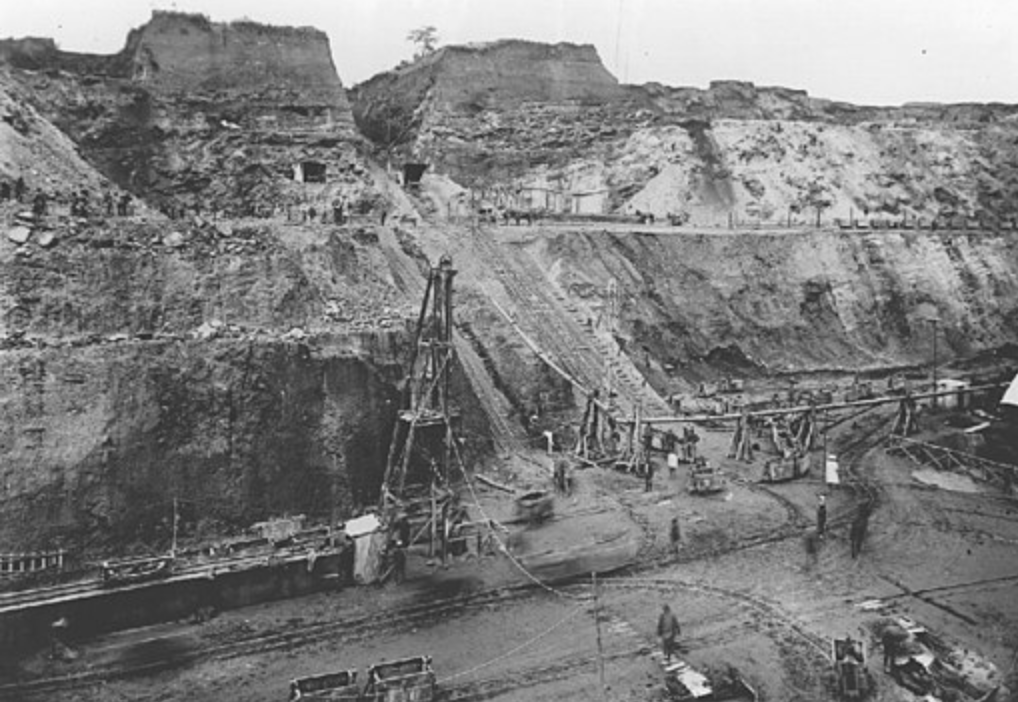

International teams of Earth Systems scientists suggested that the Earth System itself was changing based on a rapidly growing library of observations from around the world such as the temperature and salinity of both surface and deep ocean water, the flow of sediments such as nitrogen and phosphorus into coastal areas and riverbeds, the uptake of CO2, satellite pictures of shifting hydrological systems, and a range of computer modeling techniques that can simulate the climate system (Steffen et. al 2016). At the same time, scientific fields concerned with stratigraphy (the study of layered rocks for the purpose of relative dating) were making rapid advances in terms of technology and the use of novel proxies that made reliable observations about the recent past possible: technofossils (plastics, radionuclides, metals, etc.)[1], human bioturbation (particularly large-scale mining for minerals and fossil fuels), and human-mediated global energy flows (turning fossilized carbon back into a gas) to name a few examples (Williams et. al 2016). As these two fields were advancing and mixing, the utility of stratigraphic techniques for Earth Systems seeking to provide even more reliable data showing that the Earth System was changing became obvious. In 1987 the International Geosphere–Biosphere Programme (IGBP) was launched to formally “coordinate international research on global-scale and regional-scale interactions between Earth’s biological, chemical and physical processes and their interactions with human systems” (IGBP website).

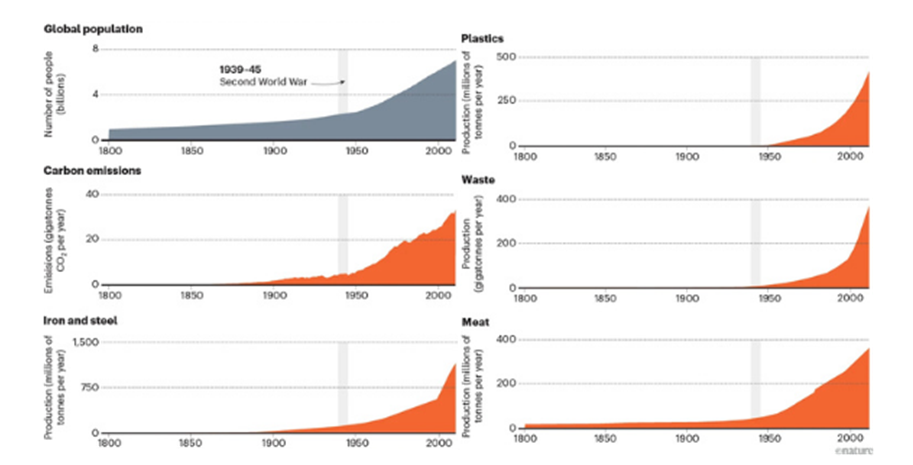

After ten years of coordination and cooperation of Earth Systems scientists and geologists under the IGBP, Crutzen and Stoermer famously declared the onset of the Anthropocene to be in the late 18th century and referenced changes in greenhouse concentrations within glacial ice cores. These new stratigraphic techniques enabled Earth Systems scientists to measure the changes at a much more granular level, which led to the community moving the base of the Anthropocene up to the mid-20th century a few years later (Crutzen and Stoermer 2000). It wasn’t that the widespread burning of coal and smelting of steel that characterized the Industrial Revolution in Europe and the United States didn’t upset the Holocene equilibrium, but that these new techniques provided scientists with evidence of an abrupt and rapid increase in disequilibrium across multiple socioeconomic and biophysical indicators starting around 1952 (see Figure 1). This was the post-World War II transition from coal to oil, testing of nuclear weapons, building interstate highways and dawn of mass consumption that would be nicknamed the “Great Acceleration” fifty years later (Zalasiewicz et. al 2021).

The Anthropocene Working Group (AWG) was established in 2009 as an official working group of the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy (SQS). It included 35 international researchers – half of whom were geologists and the rest from a diversity of fields across the social sciences, humanities, and earth sciences.[2] The AWG didn’t get funding to conduct field research until 2018, and so instead focused those early years on “studying the papers associated with previous unit formalization proposals” (Damianos 2024), starting research journals such as The Anthropocene Review (Oldfield et. al 2013), and contributing to The Anthropocene Project convened by in Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW) and the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science[3]. By 2014, Anthropocene was added to the Oxford English Dictionary and with the 2016 publication of the paper, “The Anthropocene is functionally and stratigraphically distinct from the Holocene”, in Science, and the discussion was brought firmly into public discourse – again, ahead of the field research (Waters et. al 2016, Corneliussen 2016).

As a concept or event, the Anthropocene immediately showed great flexibility in terms of identifying its starting point and the types of evidence that could be brought under its umbrella as proof of its existence. As a potential new geological epoch to be formally placed on the Geologic Time Scale, however, there were strict chronostratigraphic criteria that needed to be met for such a significant change to occur. Simply put, the Anthropocene Working Group needed to provide chronostratigraphic evidence of this shift happening all over the world at roughly the same time (Zalasiewicz et. al 2021). The boundary for a new epoch would need to be precise and measurable so that other scientists could rely on it to make meaningful observations and inferences about the Earth’s history from different locations around the world.

Evidence of human impacts – technofossils – can be found in the dispersal of polymers, fly ash, uranium, chemical pollutants and other human-made compounds that have found their way into the air, water, and land all over the planet. However, the unevenly-distributed nature of these materials makes them poor candidates for the Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP), which needs to reflect synchronicity across the planet and consequences of the human impact that are going to remain in the geologic record thousands of years from now. The AWG’s invention of the technofossil concept was essential to bridging this gap, allowing the AWG to define the lower boundary required by the GSSP: the premise of the technofossil demonstrates, in chronostratigraphic parlance, that there is nevertheless sufficient diversity of material evidence, in appropriate abundance, and adequately distributed around the world, to support the geological expression of a mid-twentieth century event, and consequently, the geological definition of an Anthropocene unit (Damianos 2024).

After five years of field research explicitly related to the Anthropocene, the AWG narrowed it down with twelve possible proxies, located in several different countries, of which one would be chosen to be the GSSP. There are several criteria that make a proxy especially suited to being a strong GSSP, including continuous sedimentation, absence of disturbance, abundance/diversity of fossils, chemostratigraphy[4], and accessibility among others, however, “annual resolution in seasonally layered archives in which layer counting can be supported by radiogenic dating techniques (e.g. 210Pb dating) or unambiguously historically dated events” are the most important for robust dating (Waters et. al 2023). Some examples of these kind of proxies that provide robust dating are anoxic marine basins and meromictic lakes, corals, ice cores and speleothems.

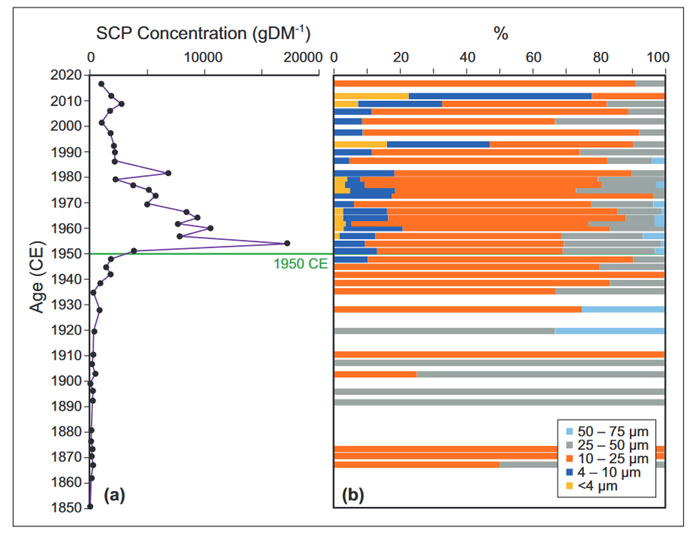

Ultimately the AWG settled on a sediment core taken from Crawford Lake in Milton, Ontario. Crawford Lake was ideal because of its unique biological and hydrological characteristics that lead to the creation of a calcite laminated layer every summer, so that annual deposition could clearly be observed. Eight cores were taken from the lake between 2011 and 2022[5], and each was analyzed using a different method: radiocarbon, palynology, varve imaging, siliceous microfossil testing, and testing for plutonium, SCPs, gamma activity, and radiocarbon. While observable changes in most of the Anthropocene proxies that were measured, the clearest marker was the sharp uptick in levels of plutonium occurring between 1950-1953 (see Figure 2). Plutonium levels increase in tandem with the testing of nuclear weapons, peaking around 1957 and then slowly declining until the 1980s when it abruptly drops (McCarthy et. al 2023).

The AWG submitted their proposal to the SQS in late 2023 and on February 1, 2024, the SQS made their decision: 12 against and 4 for[6] (El Pais 2024). According to one ethnographer who had been interviewing members of the AWG for the four years leading up to the vote, the rejection wasn’t so much about whether modern humans were making enormous measurable changes to the Earth’s biosphere as it was about rejecting a geological temporality that puts a 75-year blip on a 4.5 billion year time scale:

Voting members with whom I spoke in the weeks leading up to the AWG’s submission made clear that while they did not necessarily have a problem with, for example, radioisotopic analysis of samples that indicated an exponential increase in 239/240Pu from samples across the world, between the years 1945 and 2000 (which is a miniscule duration in the context of 4.5 billion years of Earth history), they were very sceptical about granting Epoch/Series status (thereby ending the Holocene) to a unit that might be of such a small duration as to be less than the margin of error on geological units preceding it (Damianos 2024).

For the geologist Jan Zalasiewicz, former head of the Anthropocene Working Group (2009-2020) and current chair (as of 2024) of the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy, the rejection was upsetting but not terminating. Zalasiewicz had been advocating for the Anthropocene’s inclusion as a geological epoch in research papers and essays across a range of disciplines, in interviews, public lectures, and all manner of media appearances. In addition to lodging formal complaints over procedural irregularities. Zalasiewicz would go on to write articles in popular science magazines, insisting on the urgency of the situation and the necessity of definitively marking a human-inflicted end of the Holocene in order to convince people that the environmental situation is indeed serious.

Anthropocene Common Sense as Crisis Epistemology

In August 2024 Zalasiewicz co-authored a paper in Nature summing up why the AWG’s 15-year crusade for a formal geological definition of the Anthropocene was worth it: it made the end of “the prolonged, relatively stable conditions of the Holocene” into a common sensibility (Zalasiewicz et. al 2024). What does the common sense of the Anthropocene look like expressed as a media narrative? Researchers conducting a corpus-based discourse analysis of news articles between 2000 and 2018 found that it was pretty bleak:

The overall account of the Anthropocene’s consequences displays a rather negative vision, with a prevalence of terms pointing to an unfavorable outcome, e.g., “catastrophe”, “crises”, “collapse”, “irreversible” and “extinction”. Unsurprisingly, the results are homogenous across the countries, although with due proportions in terms of quantity. Perhaps more interestingly, the word “crisis” appears several times in each country (Zottolo and Majo 2022).

Indigenous environmental philosopher Kyle P. Whyte describes crisis epistemology in terms of its two core qualities related to time: unprecedentedness and urgency (Whyte 2020a). The 25-year history of The Anthropocene’s journey from an Earth Systems scientist’s catchy neologism to potential Holocene-killer, to cultural zeitgeist would be nothing more than an academic footnote were it not for its memetic unprecedentedness and urgency. These two temporal qualities are more than just descriptors, however, they carry with them assumptions about how the crisis they relate to should be addressed by society. When an event is unprecedented – “without analog” as the Anthropocene has often been described by scientists (Zalasiewicz et. al 2021) – the implication is that there are no lessons to be learned from the past for dealing with the event. When an event is considered urgent, the need for it to be addressed quickly makes harmful externalities and the suspension of rights acceptable (Whyte 2020a).

But are periods of increased flooding, storms, droughts, and conflict unprecedented over the last 11,700 years of Holocene stability? Or is the current status quo where “the richest 1 percent [of the global population] grabbed nearly two-thirds of all new wealth worth $42 trillion created since 2020, almost twice as much money as the bottom 99 percent of the world’s population” the thing that is unprecedented (Oxfam International 2023). In universalizing the unprecedentedness, all of society is mobilized to make sacrifices and invest in protecting a status quo that is necessary for the maintenance of wealth hoarders. This means investing in dangerous “solutions” such as geoengineering that do not address the extractive relationships rooted in colonial histories, but that instead prioritize technological solutions that require intensive capitalization that only monopolistic corporations and a government with the power to print money can leverage. The compounding factor of urgency and a near-future climate collapse makes such solutions not only preferable, but necessary – regardless of their potential for dangerous externalities. It is not surprising that Crutzen himself was a big proponent of geoengineering (Crutzen 2006).

The Anthropocene does not represent an unprecedented attempt at mobilizing an apocalyptic environmental narrative that seeks to invoke a state of exception as a crisis response. In another article, Kyle Whyte recognizes similar themes in the apocalyptic narratives emanating from both non-fiction and fiction writing: “perilous futures of mass species extinctions, ecosystem degradation and social upheaval” and “dystopian times of rationing, government assistance, major extinctions, social unrest, drastic measures, and defaced landscapes” (Whyte 2018). Buell traces the rise in apocalyptic environmental narratives back to Rachel Carson’s 1962 book, Silent Spring, and Paul Erlich’s 1968 book The Population Bomb, both of which dealt in “prophetic-apocalyptic imagery and voices” (Buell 2010). Davidson and Kemp review evidence of an increasingly “desperate” public discourse of “climate catastrophe” in the 2020s, from scientists and the UN to the climate movement, linking it to models of worst-case scenarios arising from inaction (Davidson and Kemp 2023). Fagan appraises contemporary popular culture, media, and governmental texts framing climate apocalypse in terms of disaster and temporal urgency (Fagan 2017).

Masco (2017) sees a media terrain dominated by crises that bring the environmental apocalypse into everyday news cycles: “…species die-offs on an unprecedented scale; megadrought, megasnow, megacold, megaheat; proliferating toxicities and corruptions; racialized violence (state driven, terroristic, individual); stand-your-ground laws; ocean acidification, the near-eternal longevity of plastics; peak oil, peak water; smogocalypse in China…” . Swyndegow (2013) finds a pattern of “continuous invocation of fear and danger, the specter of ecological annihilation, or at least seriously distressed socio-ecological conditions for many people in the near future” in these catastrophic. Gergan, Smith, and Vasudevan (2020) explain that “impending ecological disasters in American popular imagination temporally displace the apocalypse into the present or the future…[evading] specific culpability when they imagine a universal human frailty, enacting a darkly ironic reversal of historical and ongoing apocalyptic realities.”

Crisis narratives of the Anthropocene and climate change are too numerous to count, suffice to say they exist in bulk and continue to propagate across society. Indigenous scholars have called attention to the presentist orientation of these narratives, explaining how they organize around a conception of the status quo as something that is threatened by imminent crisis. Kyle Whyte describes imminence as “the sense that something horribly harmful or inequitable is impending or pressing on the current conditions people understand themselves to be living in. There is a complexity or originality to the imminent events that suggests the need to immediately become solutions-oriented in a way believed to differ from how solutions were designed and enacted previously” (Whyte 2020). I feel the pressure of imminence in my own field of Sustainability, as we are encouraged to “find practical solutions” to address climate change “within the system” that currently exists. Concerning oneself too much with the negative externalities of technological solutions or the exponential concentration of wealth that has occurred since The Great Recession – or the enslaved people working in Congo’s mines – is a surefire way to not get a job.

CONCLUSION

On March 5, 2024, the NY Times ran an article with the pithy title, Are We in the ‘Anthropocene,’ the Human Age? Nope, Scientists Say, about the vote that had recently been taken by the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy (SQS) on whether to definitively mark the end of the Holocene Epoch on the geological time scale and initiate the Anthropocene (Zhong 2024). The article explains how the geological time scale is organized, how changes are made to it, and the different ways researchers conceptualize the Anthropocene in their work. While the title seems to imply a universal consensus among scientists, the article quotes an environmental scientist who is very clear that this vote is inside baseball – a narrow procedural vote about classification involving a small subset of geologists. The background story of the Anthropocene Working Group reveals that the stakes are much higher than an academic quarrel.

The Anthropocene story represents a concerted effort among experts to institutionalize a universal narrative of culpability for the destabilization of Earth’s systems in a way that masks colonial power relations. Rather than a description of observable scientific facts, data about changes to Earth’s systems is pulled into a crisis narrative as evidence of an unprecedented destabilization that is inevitably leading to a dystopian future that 9 billion individuals are collectively responsible for preventing. This dark future imaginary casts the interconnected environmental crises that are unfolding as temporally and existentially novel, rather than a continuation of “previous eras that begin with colonialism and extend through advanced capitalism” (Whyte 2017).

This novel dystopian future is suffused with urgency, a demand that creates a state of exception that overrides demands for justice, reparation, democracy, and human rights. Technological solutions that do not disturb the political economic status quo are prioritized over systemic change, as we can see in public investment in geoengineering, carbon capture, green energy, and electric vehicles. Championing any policy that might inhibit the economic growth of the fossil fuel industry or regulate private corporations – the institutions responsible for the most emissions and as such are the only ones truly capable of reducing the nation’s carbon footprint – is career suicide for an academic or politician in a system where bribery is the norm. Future destabilization of the status quo becomes a security risk, demanding a response from the only public institution whose budget is immune from both austerity and accountability: the military.

The Anthropocene crisis narrative is thus inherently political, even as it positions itself as just reporting the facts. Rather than mobilizing concern for our common home to demand changes to the relationships and power structures that created the crisis in the first place, the Anthropocene narrative engenders an overwhelming sense of inevitability, doom, and dependency among individual members of the universally culpable human species. It locks us in a state of exception, forgetting that for the many millions of victims of colonialism, genocide, slavery, imperialist wars, manufactured famine, resource extraction, and industrial contamination, many apocalypses have already happened and the people who caused them have names.

REFERENCES

Buell, F. (2010). A Short History of Environmental Apocalypse. In Future ethics: climate change and apocalyptic imagination. Continuum.

Chemostratigraphy – an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2024, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/earth-and-planetary-sciences/chemostratigraphy

Corneliussen, S. T. (2016). Media attention increases for the term—and concept—Anthropocene. https://doi.org/10.1063/PT.5.8194

Crutzen, P. J. (2006). Albedo Enhancement by Stratospheric Sulfur Injections: A Contribution to Resolve a Policy Dilemma? Climatic Change, 77(3), 211–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-006-9101-y

Crutzen, P. J., & Stoermer, E. F. (2000). The “Anthropocene”. IGBP Global Change Newsletter, 41, 17–18.

Damianos, A. (2024). Anthropocene angst: Authentic geology and stratigraphic sincerity. Social Studies of Science, 03063127241282309. https://doi.org/10.1177/03063127241282309

Davidson, J. P. L., & Kemp, L. (2024). Climate catastrophe: The value of envisioning the worst-case scenarios of climate change. WIREs Climate Change, 15(2), e871. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.871

EL PAÍS English. The Anthropocene war: The controversial vote that decided not to change the planet’s geological epoch. Retrieved December 10, 2024, from https://english.elpais.com/science-tech/2024-03-08/the-anthropocene-war-the-controversial-vote-that-decided-not-to-change-the-planets-geological-epoch.html

Fagan, M. (2017). Who’s afraid of the ecological apocalypse? Climate change and the production of the ethical subject. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 19(2), 225–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148116687534

Gergan, M., Smith, S., & Vasudevan, P. (2020). Earth beyond repair: Race and apocalypse in collective imagination. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 38(1), 91–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775818756079

Haff, P. (2014). Humans and technology in the Anthropocene: Six rules. The Anthropocene Review, 1(2), 126–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053019614530575

Masco, J. (2017). The Crisis in Crisis. Current Anthropology, 58(S15), S65–S76. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26544377

McCarthy, F. M., Patterson, R. T., Head, M. J., Riddick, N. L., Cumming, B. F., Hamilton, P. B., Pisaric, M. F., Gushulak, A. C., Leavitt, P. R., Lafond, K. M., Llew-Williams, B., Marshall, M., Heyde, A., Pilkington, P. M., Moraal, J., Boyce, J. I., Nasser, N. A., Walsh, C., Garvie, M., … McAndrews, J. H. (2023). The varved succession of Crawford Lake, Milton, Ontario, Canada as a candidate Global boundary Stratotype Section and Point for the Anthropocene series. The Anthropocene Review, 10(1), 146–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/20530196221149281

Oldfield, F., Barnosky, A. D., Dearing, J., Fischer-Kowalski, M., McNeill, J., Steffen, W., & Zalasiewicz, J. (2014). The Anthropocene Review: Its significance, implications and the rationale for a new transdisciplinary journal. The Anthropocene Review, 1(1), 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053019613500445

Oxfam International. Richest 1% bag nearly twice as much wealth as the rest of the world put together over the past two years. (2023, September 4). https://www.oxfam.org/en/press-releases/richest-1-bag-nearly-twice-much-wealth-rest-world-put-together-over-past-two-years

Schellnhuber, H. J. (1999). “Earth system” analysis and the second Copernican revolution. NATURE, 402(6761), C19–C23. https://doi.org/10.1038/35011515

Steffen, W., Leinfelder, R., Zalasiewicz, J., Waters, C. N., Williams, M., Summerhayes, C., Barnosky, A. D., Cearreta, A., Crutzen, P., Edgeworth, M., Ellis, E. C., Fairchild, I. J., Galuszka, A., Grinevald, J., Haywood, A., Ivar do Sul, J., Jeandel, C., McNeill, J. r., Odada, E., … Schellnhuber, H. j. (2016). Stratigraphic and Earth System approaches to defining the Anthropocene. Earth’s Future, 4(8), 324–345. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016EF000379

Swyngedouw, E. (2013). Apocalypse Now! Fear and Doomsday Pleasures. Capitalism Nature Socialism, 24(1), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10455752.2012.759252

Waters, C. N., Turner, S. D., Zalasiewicz, J., & Head, M. J. (2023). Candidate sites and other reference sections for the Global boundary Stratotype Section and Point of the Anthropocene series. The Anthropocene Review, 10(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/20530196221136422

Waters, C. N., Zalasiewicz, J., Summerhayes, C., Barnosky, A. D., Poirier, C., Gałuszka, A., Cearreta, A., Edgeworth, M., Ellis, E. C., Ellis, M., Jeandel, C., Leinfelder, R., McNeill, J. R., Richter, D. deB., Steffen, W., Syvitski, J., Vidas, D., Wagreich, M., Williams, M., … Wolfe, A. P. (2016). The Anthropocene is functionally and stratigraphically distinct from the Holocene. Science, 351(6269), aad2622. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad2622

Whyte, K. (2020). Against crisis epistemology. In B. Hokowhitu, A. Moreton-Robinson, L. Tuhiwai-Smith, C. Andersen, & S. Larkin (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Critical Indigenous Studies (1st ed., pp. 52–64). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429440229-6

WHYTE, K. P. (2017). Our ancestors’ dystopia now: indigenous conservation and the Anthropocene. In The Routledge Companion to the Environmental Humanities. Routledge.

Whyte, K. P. (2018). Indigenous science (fiction) for the Anthropocene: Ancestral dystopias and fantasies of climate change crises. Environment & Planning E: Nature & Space, 1(1/2), 224–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/2514848618777621

Williams, M., Zalasiewicz, J., Waters, C. N., Edgeworth, M., Bennett, C., Barnosky, A. D., Ellis, E. C., Ellis, M. A., Cearreta, A., Haff, P. K., Ivar do Sul, J. A., Leinfelder, R., McNeill, J. R., Odada, E., Oreskes, N., Revkin, A., Richter, D. deB, Steffen, W., Summerhayes, C., … Zhisheng, A. (2016). The Anthropocene: a conspicuous stratigraphical signal of anthropogenic changes in production and consumption across the biosphere. Earth’s Future, 4(3), 34–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015EF000339

Zalasiewicz, J., Adeney Thomas, J., Waters, C. N., Turner, S., & Head, M. J. (2024). The meaning of the Anthropocene: why it matters even without a formal geological definition. Nature, 632(8027), 980–984. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-02712-y

Zalasiewicz, J., Waters, C. N., Ellis, E. C., Head, M. J., Vidas, D., Steffen, W., Thomas, J. A., Horn, E., Summerhayes, C. P., Leinfelder, R., McNeill, J. R., Gałuszka, A., Williams, M., Barnosky, A. D., Richter, D. de B., Gibbard, P. L., Syvitski, J., Jeandel, C., Cearreta, A., … Zinke, J. (2021). The Anthropocene: Comparing Its Meaning in Geology (Chronostratigraphy) with Conceptual Approaches Arising in Other Disciplines. Earth’s Future, 9(3), e2020EF001896. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020EF001896

Zhong, R. (2024, March 5). Are We in the ‘Anthropocene,’ the Human Age? Nope, Scientists Say. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/03/05/climate/anthropocene-epoch-vote-rejected.html

Zottola, A., & Majo, C. de. (2022). The Anthropocene: genesis of a term and popularization in the press. Text & Talk, 42(4), 453–473. https://doi.org/10.1515/text-2020-0080

[1] Dr. Peter Haff, Professor Emeritus of Earth and Climate Sciences at Duke University and former member of the AWG authored a paper in August 2014 for The Anthropocene Review, “Humans and Technology in the Anthropocene: Six Rules”, and co-authored a paper with the other members of the AWG in April 2014 for Anthropocene Review, “The Technofossil Record of Humans”, which jointly coined the technofossil term that would go on to be used in the AWG’s publications as a chronostratigraphic evidence. Technofossils are the material remains of what AWG members call the technosphere.

[2] The SQS website hosts a legacy site of the AWG’s past activities, including all former members: quaternary.stratigraphy.org/working-groups/anthropocene

[3] The Anthropocene Project (2013-2014) was organized around this idea: “Our notion of nature is now out of date. Humanity forms nature. This is the core premise of the Anthropocene thesis, announcing a paradigm shift in the natural sciences as well as providing new models for culture, politics, and everyday life. In a two-year project (2013/2014), HKW explored the hypothesis’ manifold implications for the sciences and arts. Cooperations and events in Berlin and all over the world continue the debate on the Anthropocene” (HKW 2013).

[4] Chemostratigraphy is the study of “chemical variations within the sedimentary sequences, either based on the elemental or isotopic composition of the rock” (Craigie 2021).

[5] Some of the cores were taken and stored by other scientists studying Crawford Lake prior to the commencement of AWG’s field research in 2018

[6] There were also 2 abstentions and 3 non-abstention/non-votes.